Chapter 2

I write when I’m angry. I’m not very confrontational, so when I feel angry, I tend to bottle it up. At least, until my thoughts unravel on the page.

The first time I felt angry in the wake of Borderline and the fires was when I was in class, writing notes. Actually, I spent most of my time looking at my phone. News about the Hill Fire was starting to break.

I wasn’t the only student distracted, because my only memory of that class is my professor threatening to give us a pop quiz. In that moment, I wanted to yell at him. I couldn’t process the shooting yet, let alone the fires approaching my friends and family, let alone the lecture my goofy yet upsetting professor was about to give me a pop quiz on.

I recognize now that that’s only one way my anger manifested. Anger can feel like confusion, or like panic, or like wanting to shut down completely. In talking with other community members, I’ve seen so many different emotions that I don’t think “anger” fully covers it.

But on that day, I skipped my third class. News about the Woolsey Fire was starting to break.

“Only hours after a gunman attacked a country music bar in Thousand Oaks, the city was once again struck with panic. This time, fire forced the evacuation of the town still reeling from the devastating shooting.”

This quote comes from the November 9th, 2018 CNN article by Jennifer Medina, Jose A Del Real, and Tim Arango titled, “‘It Really Can’t Get Much Worse’: Thousand Oaks, First Hit by Shooting, Now Faces Fire”.

“When we got back to that station, right after it [the shooting], my phone was ringing off the hook. Everybody wanted to know what was going on, what happened, everybody somehow found out that I was there. For us, as firefighters, when those kinds of calls go down, we don't want to talk to anybody. It's just kind of a mechanism for us. It's hard for me to explain to you what it was like when you don't go through that in your normal life.”

-Chris Sharp, Ventura County firefighter

In the early morning after the Borderline shooting, Sharp remembers returning to Station 35, his station at the time, only beginning to process what he had experienced. A few hours later, the Hill and Woolsey fires started, forcing him to focus on even more people in danger.

“I got on the road to go back to Thousand Oaks [from Arizona]. Three or four hours in was the first time I got a phone call. Some of them were, ‘Were you there? Are you okay?’ Other ones were like, ‘This person's missing.’ It started to get really scary... then I got the big phone call that it was confirmed that Kristina [Morisette] was killed. From that point forward, it was impossible to want to answer the phone anymore, because I didn't want to hear someone say that someone else was killed.”

-Luke Besselo, University of Arizona student, Borderline attendee

Later on in his drive from Tucson to Thousand Oaks, Besselo got another call from a friend that confirmed that someone else they knew, Justin Meek, was also one of the victims.

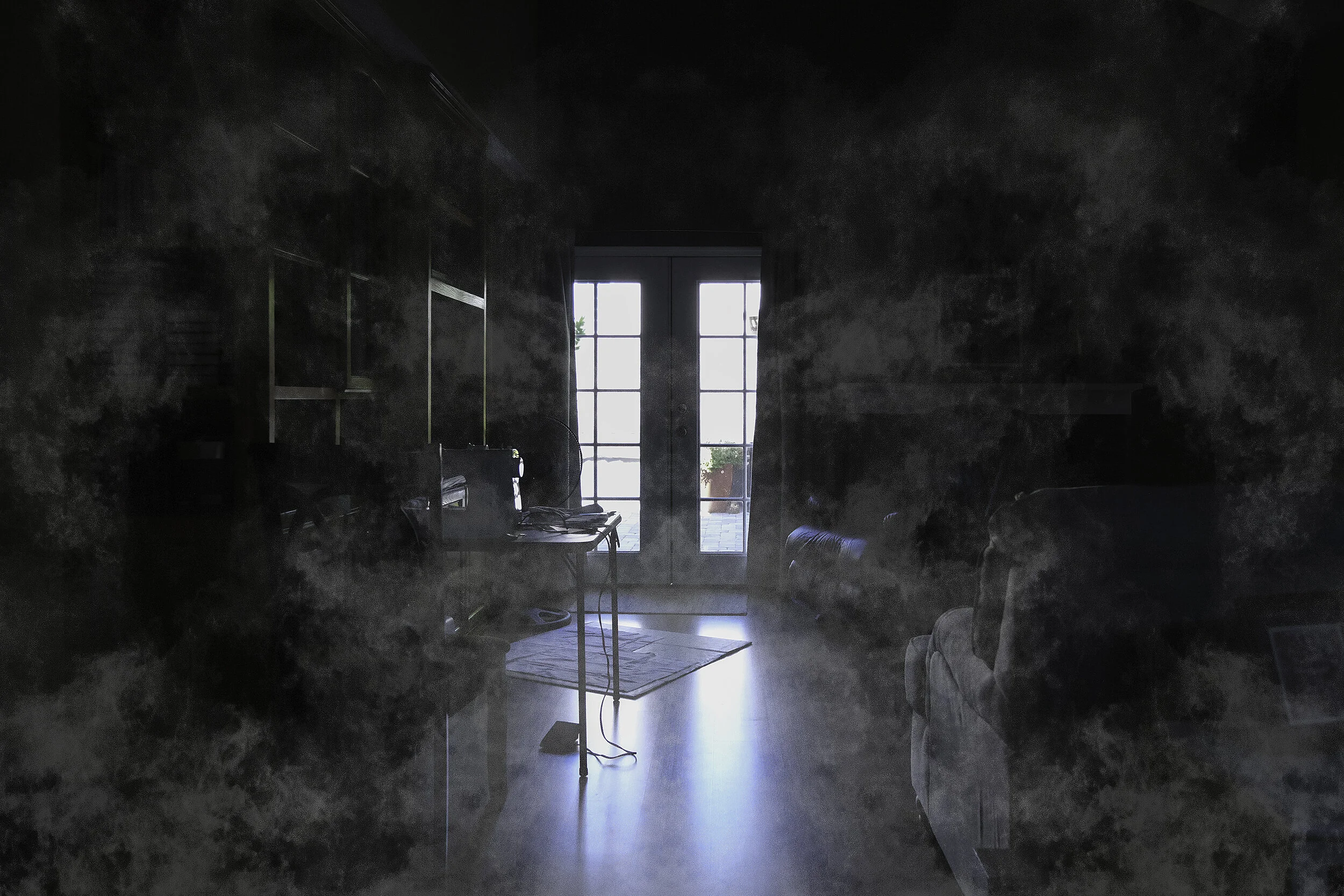

“We were on the ladder truck, so it's a little bit of an apparatus than a normal engine... We were in a support role. We would go into neighborhoods, there would be engines fighting the fires or protecting homes, and if there was a house on fire, we would [help with] that... There was a house that we came to where a guy was just standing there. It was so smoky that he didn't know what to do.”

-Chris Sharp, Ventura County firefighter

“It’s obviously very traumatic, it’s very personal, and at the same time it can be infuriating… It’s not just an issue of trying to deal with the death of your kid… the context in which all this came down is not being addressed by the powers at be.”

-Marc Orfanos, father of Telemachus Orfanos

Though the Hill and Woolsey Fires did not directly impact the Orfanos family, their home was shaken by the loss of their son, Telemachus, at the Borderline shooting. In the days and weeks that followed, the lack of action by government officials to pass gun control legislation became even more upsetting.